During my early elementary school years in Memphis, Tennessee, seems like every child around me showed up to class at one point or another grinning ear to ear, eager to announce the arrival of a new infant sibling in the house. Then on a special afternoon that kid’s mama would step into our cinder-brick public school classroom holding the swaddled infant whilst the older brother or sister joined her up in front of the teacher’s desk and everyone swooned over the tiny ball of pink squirminess; maybe she’d walk up and down the rows of desks with big brother or sister at her skirt hem so the kids could have a closer look. Every child was insanely jealous, or so I assumed because I certainly was. Many of my classmates had older siblings, too, a thing I couldn’t fathom, being the oldest myself.

With each passing year, though, my dream of a younger sibling drew closer to an imagined vanishing point on the horizon that signaled the mystery that was The Rest of My Life. In my mind’s eye she had always been a girl with long, golden locks of hair (unlikely, but I had no grasp of genetics). The chief purpose of this child, to my six-year-old way of thinking, was simply to assuage my need to fiddle with all that hair—to braid it, twist and pile it, pin it, ponytail it, beribbon and barrette it, and otherwise do it up to my heart’s content.

I believe my family understood this desire, because one year Santa brought me a child-size Barbie bust whose sole purpose was…hair fiddling. Another year I was gifted this curiosity called a fall—not a wig, but a hair attachment clipped to one’s own hair to give the illusion of length. Somewhere is a snapshot of me standing about halfway up our stairs with the fall draped dramatically over one shoulder. I am wearing my favorite outfit at the time, a pair of stretchy, Holly Golightly-style mustard-colored stirrup trousers and matching striped turtleneck.

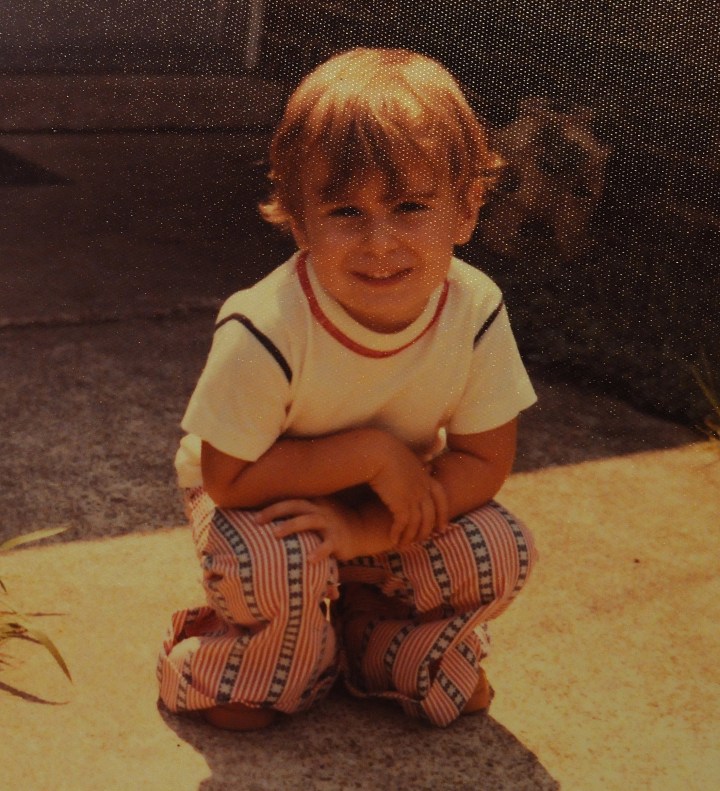

Thing is, the ‘fall’ looked not one little bit real or convincing, but for a few moments in my life I suppose gave me some happiness. The rule in my family was, yes, you can have long hair, punkin, just as soon as you can take care of it yourself (bless your heart). So like others during this era that straddled the late ’60s and early ’70s, I was left to make my peace with the ‘pixie’ cut. I hated it in spite of the consensus in my family that I was “cute as a button.”

I digress.

Imagine my excitement when my parents finally announced to me sometime in early 1969 that I’d gain membership to the exclusive league of big sisters! and not one moment too soon, as I’d be entering second grade that fall. I watched with delight as my mama’s belly grew round, anticipating all the flurry of welcoming my new baby sister, not dissuaded for an instant after my parents had ‘named’ the unborn child “Who’s-He-What’s-It” because we just didn’t know. It was of course a girl.

Except of course It was not. On the November afternoon my mama gave birth to baby number two, a healthy boy with a cranky disposition from the get-go, I had been farmed out to my godparents’ home, there to stay out of everybody’s hair when all I really wanted was to be into my new little sister’s hair. The phone rang, my godmother answered, and then handed me the receiver. I do not recall who was on the other end—probably dad—because I stopped listening after “brother” and handed it back, crushed under the weight of my burgeoning disappointment. I had no interest in a baby boy and anyway suddenly considered myself too old and sophisticated for this silly younger sibling business. What on earth could I do with this interloper.

In time I grew at least some enchanted by all the new procedures and routines in our household, the smell of talcum powder and clean, hot cotton diapers just out of the dryer, and all the rest for which my parents had prepared me as much as anybody did their older kids in those days. A brochure from our pediatrician described (in sanitized language that betrayed exactly nothing) the process of conception, fetal development, and childbirth, leaving more questions in my young mind than answers. And here was a saccharine-sweet book handed to me by somebody, entitled, Babies Are Like That—essentially an elegant warning that the new kid would most definitely be a pain in the ass and would upstage me in every conceivable way.

There was this: I finally had my moment at the front of Mrs. Pete’s second-grade classroom at Fox Meadows Elementary School, standing next to my mama, who held my sleeping infant brother in her arms. Gloating in the limelight, if only for an instant, is so satisfying when you’re seven.

But seven years are many years to stretch between sibs. A long time later I’d attend a parenting class and learn the tenets of Murray Bowen’s Family Systems Theory, which maintains that when more than five years separate two children in a family, then each of them is considered an ‘only’ emotionally. Explains a lot, if you subscribe to that one. Seems plausible enough to me. I never developed the same tight bond with my baby brother I observed between siblings in some of my friends’ families, where the children were stair-stepped by only a couple years each (looking at you, Catholic pals).

Not long after my brother’s arrival, though, I questioned this disparity and unseemly length of time. What took so long? I wondered aloud, Because you must now realize this younger boy sibling thing won’t work at all.

You were an accident, came the answer. Your brother was planned. The implicit memo was, we’d have waited longer to have you had we planned your arrival rather than just being careless and sloppy.

I was left to think on that one. It does not take long, gentle reader, to conflate accident with mistake in the mind of a seven-year-old kid. I was savvy enough to hear that message, even if it was unintentional.

There was another heaping disparity that threw buckets of gasoline on that fire and then fanned the flames, but that is a story for another day. Suffice it to say we settled into our family life with the new baby, I grew up as emotionally unscarred as anybody and hopefully so did my brother—he seems okay to me—and I emerged from that experience with wisdom that carried over into how I parented my own child decades later.

That clichéd quip about everything in your life preparing you for a particular moment? Truth. Because if I felt slighted by the implication I had been an accident, imagine how an adopted child must wrestle with a thing far more profound—the notion of rejection—and can there be any more powerful guise of rejection than being surrendered to another family by one’s own birth parents? It is at the same time the most selfless act of love, a paradox that impossibly muddies the message. Knowing you must someday explain it to the child, though, was the monumental epiphany that quite literally landed in my lap on a cold day in March of 1993.

Language is powerful as much as all the little facial expressions and gestures and tics baked into our families. We are left to ponder these and to gain valuable insight into who we are, but not to dwell on them else they’ll eat us alive—no parent or sibling deserves that much power.

Postscript: I fully expect my parents might have a completely different take on all this now, also my brother; this story is mine alone, and doesn’t that just dovetail beautifully with the emotional intelligence of an ‘only’ child.